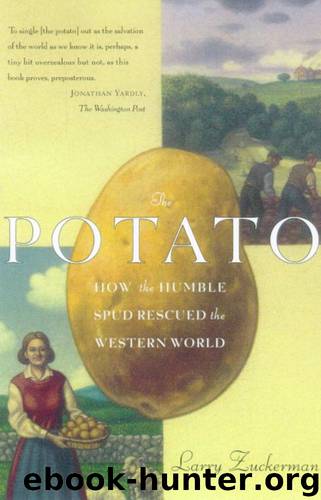

The Potato by Larry Zuckerman

Author:Larry Zuckerman

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Faber & Faber

Published: 2012-02-02T16:00:00+00:00

The memory of famine, so vivid that decades of relative security couldn’t erase it, formed a large part of what inspired the peasantry to save and conserve. The threat of want settled under rural roofs like a despotic houseguest whose orders must be followed despite inconvenience or suffering. Even during the 1880s and 1890s, when French agriculture had arguably reached its most prosperous point of the century, people were still recalling disasters from the Restoration era. In Haute-Marne they talked about 1816, when they had to eat barley bread made with beans, which rattled around inside the loaves. A villager from the Gard said that everyone kept famine in mind because you could easily count the houses where people ate well. Stories circulated in the Mâconnais about the hailstorm of 1817, which destroyed the grain and forced the most desperate to try to make bread out of ground-up walnut shells.

But it wasn’t necessary to reflect on the past; the present could be terrifying. Like the English and Irish peasantries, the French constantly battled debt and a bare larder. Arthur Young was told in 1790 that sharecroppers in Berry “almost every year borrowed their bread of the landlord before the harvest came round.” It was bad bread, too, he said. As for their Limousin counterparts, he heard that they did no better. Half of them were deep in debt to their landlords, who felt obliged to turn their tenants out and take a loss. Sharecropping covenants typically favored the landowner, but even without that disadvantage, the farmer’s resources were easily stretched. Needing money, he might have to sell his grain right after the harvest, when the market was lowest, only to have to buy it back after the price had risen. Laborers who had little or no land were even worse off, because their wages didn’t always cover their needs, as an 1848 inquiry discovered in the Nivernais. The economy did improve during the century’s second half, but debt remained a danger. A woman who grew up in the Nord in the 1890s recalled that everyone in the family earned wages—they even worked on Christmas—yet they still lived all winter on credit. A man born near Chartres in 1897 remembered that his mother earned fifty centimes a day sewing, while land rented at twenty-five francs the hectare (a low figure, incidentally). To make ends meet, his parents “worked almost like serfs.” Joseph Cressot, who grew up in late-nineteenth-century Haute-Marne, remarked that the land let you live if you lived simply. For Cressot’s family, who were poor but not hungry, simplicity sufficed. For the less lucky, it didn’t.

As in other peasant economies, cash was scarce. Farm wages were low. Many laborers lived with their employers, who paid them in money and kind, and gave free board, lodging, and laundry. The arrangement sounds more generous than it was. In 1852 annual money wages averaged anywhere from less than 100 francs to slightly more than 200, depending on local custom. Ten years later, the national average approached 200 francs, a needed improvement.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12080)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5357)

Navigation and Map Reading by K Andrew(5147)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4381)

Barron's AP Biology by Goldberg M.S. Deborah T(4137)

5 Steps to a 5 AP U.S. History, 2010-2011 Edition (5 Steps to a 5 on the Advanced Placement Examinations Series) by Armstrong Stephen(3721)

Three Women by Lisa Taddeo(3416)

Water by Ian Miller(3172)

The Comedians: Drunks, Thieves, Scoundrels, and the History of American Comedy by Nesteroff Kliph(3064)

Drugs Unlimited by Mike Power(2584)

A Short History of Drunkenness by Forsyth Mark(2282)

DarkMarket by Misha Glenny(2203)

The House of Government by Slezkine Yuri(2190)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(2183)

The Library Book by Susan Orlean(2061)

Revived (Cat Patrick) by Cat Patrick(1984)

The Woman Who Smashed Codes by Jason Fagone(1955)

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie(1899)

Birth by Tina Cassidy(1899)